One way to grieve a death is to think about the deceased and consider activities they did that you would like to continue in their memory. It may be making a certain recipe for holidays, volunteering where they used to, or eating Coney Island hot dogs on their birthday. This is a way to keep their memory alive and give us a reason to tell others about the person we are memorializing. My sister, Joan, was a wonderfully talented seamstress, artists, educator, and master gardener. When she died, I had several aspects of her life that I could choose to continue in her honor, but not many that I was talented enough to do well.

I had always admired the jewelry that she made and still have the earrings she made me while I was in high school. So, to honor Joan, I decided to learn how to make jewelry, particularly modern mourning jewelry.

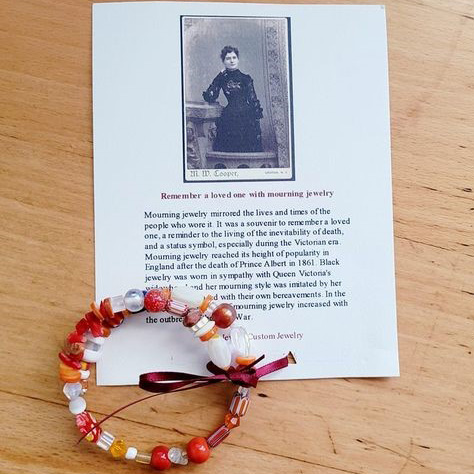

Mourning jewelry became fashionable in the 1800’s. The death of Queen Victoria’s beloved Albert in 1861 began a forty-year period of mourning for The Queen and an increased popularity of mourning jewelry throughout Great Britain. While some observed a period of mourning that had an end, many continued to wear mourning jewelry the rest of their lives as a demonstration of the depth of their grief and loss.

Human hair was incorporated into jewelry in the early 1800’s and was often given as a token of love but was also worn as mourning jewelry. Victorian hair jewelry ranged from lockets with a lock of a loved one’s hair to jewelry delicately woven and braided into works of art.

The wearing of black mourning jewelry became popular in the United States during the Civil War. With so many loved ones off to war, it was not uncommon for a departing soldier to leave a lock of hair with a loved one which was usually worn in a gold or silver locket and transferred to a black locket if the soldier died.

Historically we had outward symbols to let people know were grieving (e.g., black arm bands, dressing in all black for months or years, men not shaving for 40 days, mourning jewelry). These practices are no longer followed, so unless we say that there has been a death, it can be unknown to people we encounter. And with that we have lost the opportunity to share our story and receive comfort and condolences.

My way of memorializing my sister has been to make the bereaved a piece of handmade jewelry. When people comment on it and the wearer can say “I received this when my mother died” which opens the conversation about this loss.

It has been nearly 20 years that I have been making mourning jewelry, and unlike some of my projects, this one has turned out as I imagined. Many of my friends and colleagues have purchased them to share with their family and friends. The idea resonates with people, and it sparks the conversation and support that I hoped for. We are giving away mourning jewelry as prizes in our monthly drawings, so be sure to subscribe to our newsletter.

I would love to hear your thoughts about this project in the comments, reach out in social media, or email me at: marianne@every1dies.org

Does this give you some ideas?

Here’s a few introductory videos on beading your own bracelets:

Resources:

- Mourning in the Nineteenth Century: An Overview by Virginia Messenger – reproduced from The Campbell Crier, the newsletter of the 42nd Virginia Infantry Regiment March 1998 issue.

- Mourning in the 19th century – Connecticut Historical Society

- How to Identify Victorian Mourning Jewelry – Sprucecrafts

- Trendy Victorian-Era Jewelry Was Made From Hair – National Geographic