We often use words like fighting, battle, and war for illness like cancer, but is it fair? Battles have winners and losers, and our labels destine hard “fighters” to feel like a failure when illness advances. The harm is treatment is continued to the bitter end at any cost: emotionally, socially and financially. Can we do better?

Will people be disappointed in me for not “fighting” hard enough?

Xeni Jardin, a breast cancer survivor, wrote an opinion for CNN titled “Why cancer is not a war, fight, or battle.” Charlie read an excerpt, included below. As you read it think about how our choice of words affects people living with disease:

“Why cancer is not a war, fight, or battle” (Excerpt) Xeni Jardin I’m a cancer survivor, and since the day of my own diagnosis, it felt strange to hear: “You’ll beat this.” “You got this.” “You’ll win this battle.” “Cancer isn’t as tough as you.” “You have a positive attitude and you’re a fighter, so I know you’ll get well soon.” “You’ll be fine.” Strangers and friends who loved me said some of these things. I knew they meant well. Like them, I grew up hearing cancer described as combat, something you “beat” if you’ve got enough “fight” in you. President Richard Nixon declared war on cancer when I was a baby. Military metaphors were familiar, but they stopped making sense when the war was me. My own body. Cancer, I soon learned, is my own cells going rogue. Suddenly all the combat language was confusing. Am I the invading army or the battleground? Am I the soldier or a hostage the soldier’s trying to liberate? All of the above? If the chemotherapy and radiation and surgery and drugs don’t work, and I die, will people be disappointed in me for not “fighting” hard enough? For me, cancer never felt like a war. Cancer wasn’t something I “had,” but a process my body was going through. Brutal but effective medical treatment paused that process, as far as I know today. By the grace of science and God, I’m alive with no evidence of active disease as I share these words. It’s as close to “cured” or “winning” as I get, one day at a time. And I’ll take it, with gratitude. In war, we are taught, there are winners and losers. When breast cancer, a disease for which there is no known cure, progresses to our lymph nodes and shuts down our organs, have we as fighters failed? There’s no one right thing to say when someone gets diagnosed with cancer. Even if there were, nobody elected me to be the cancer vocabulary police. I am no warrior. I just showed up to my medical appointments, did what I was told, and lived as best I could. Now, I try to avoid saying things to other cancer patients that imply I expect a certain outcome for them, or that I expect them to feel or behave in a particular way. “Try to think positive!” isn’t always reasonable or possible, and I don’t want to make a fellow patient feel bad by commanding them to feel one thing or another. Some of the fellow cancer patients I met online became close friends during the isolation of treatment. They freely shared invaluable tips from their own cancer experience that helped me have a good outcome. Some of these men and women didn’t live. Their cancers didn’t respond to treatment, or they did but later popped back up as metastatic recurrences. Some of those stage IV patient friends have since died. They taught me that acceptance of the unknowable, and doing our best with our bodies, our lives, and our treatment options a day at a time is the best any of us can do. One of those beautiful friends was Lisa Adams, a mother and writer, and a fearless soul. “When I die don’t say I ‘fought a battle.’ Or ‘lost a battle.’ Or ‘succumbed,” she wrote. Don’t make it sound like I didn’t try hard enough, or have the right attitude, or that I simply gave up. When I die tell the world what happened. Plain and simple. No euphemisms, no flowery language, no metaphors.” She lived. She died. She is still loved. Her words still resonate for me. During this odd era in which facts, truth, and reality itself seem to be up for grabs, I’d like to propose that with cancer, as Lisa suggested, we just call it what it is. War is war. Cancer is cancer. Cancer is a disease of cellular biology in which some cells stop obeying the good instructions they’ve been given. They hog the body’s shared resources, and replicate over and over again, until the body’s own organs cannot carry out the basic functions we need for life to continue. We don’t know how any cancer patient’s life will unfold. What will become of any one of us is not ours to know. All that any of us can do is try to live today as best we can.

Why Do we “Fight” Cancer?

As a nurse practitioner Dr. Matzo worked for many years with people who were living with cancer. Not fighting cancer, not battling cancer, but living with cancer. These people, along with family and friends, would often use the language of the ‘fight against cancer’. But this metaphor never made sense to her. What are we fighting against? How do you fight against random diseases?

Cancer is Explained Primarily as Just “Bad Luck”

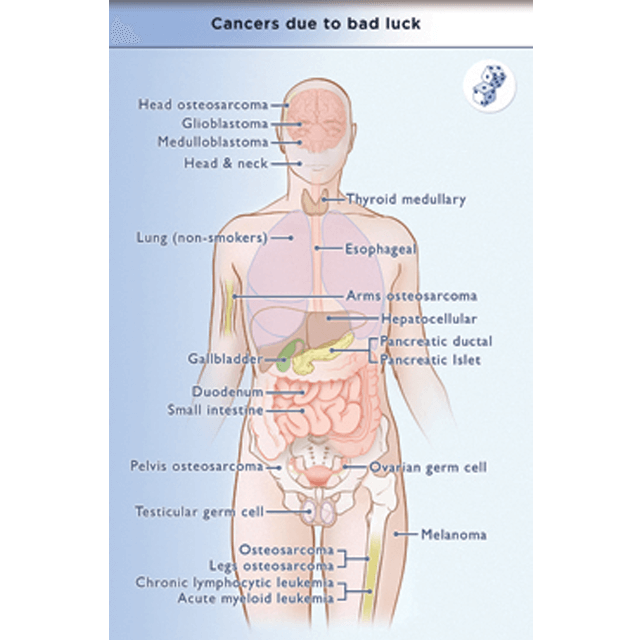

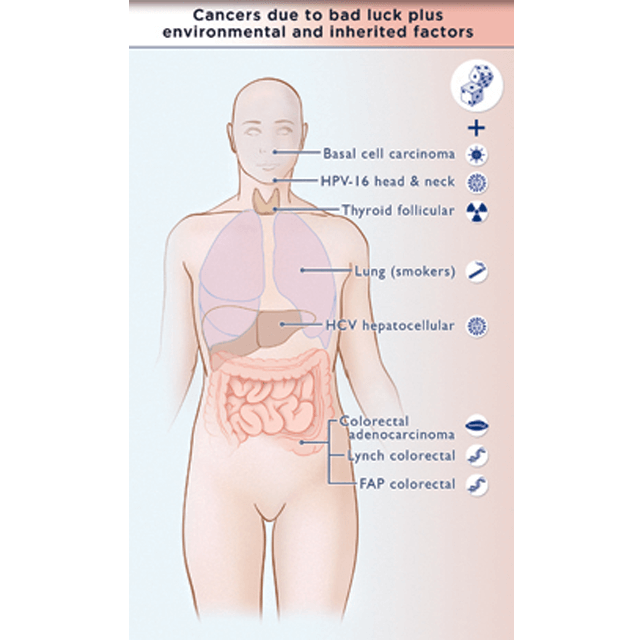

Using a statistical model that measured the proportion of cancer risk, across many tissue types, scientists from the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center published a study in 2015 which concluded that two-thirds of the variation in adult cancer risk across tissues can be explained primarily by “bad luck.” In other words, a major contributing factor to cancer is beyond our control.

Authors of the study share this metaphor:

“Getting cancer could be compared to getting into a car accident. Our results would be equivalent to showing a high correlation between length of trip and getting into an accident. Regardless of the destination, the longer the trip is, the higher the risk of an accident.

The road conditions on the way to the destination could be likened to the environmental factors in cancer. Worse conditions would be associated with a higher the risk of an accident.”

“The mechanical condition of the car is a metaphor for the inherited genetic factors. The numbers of mechanical problems in the car—bad brakes, worn tires, etc.—increase the risk of an accident. Think of these mechanical problems as inherited genetic mutations. With each mechanical defect, the risk of an accident increases. Similarly, the amount of inherited genetic mutations is among the factors that contribute to cancer risk.

Now, consider the length of the trip. This could be likened to the stem cell divisions and random mutations we discuss in our paper. Even with bad road conditions and driving a car in disrepair, the length of the trip plays a significant role. An extremely short trip has an accident risk close to zero. Regardless of road and car conditions, the probability of an accident occurring increases with distance traveled. Short trips have the lowest risk, while long trips are associated with the highest risk.

Using this analogy, we would estimate that two-thirds of the risk of getting into an accident is attributable to the length of the trip. The rest of the risk comes from bad cars, bad roads and other factors. In terms of cancer, we calculate that two-thirds of the variation is attributable to the random mutations that occur in stem cell divisions throughout a person’s lifetime, while the remaining risk is associated with environmental factors and inherited gene mutations. “

Some people may feel relief in this research finding. Cancer has a long history of stigmatization. Patients and family members frequently blame themselves, believing there was something they could have done to prevent their or their family member’s cancer. These findings may bring comfort and even lift the burden of guilt on those who have endured the physical and emotional consequences of cancer.

Can we move how we talk about serious illness to the DMZ?

We propose that serious illnesses, including cancer, be moved to the DMZ, the demilitarized zone, which is an area from which warring parties agree to remove their military forces. Serious illnesses are diseases and not a military campaign. Surviving is not an act of will, if it were, much fewer people would ever die. Friends and family mean well when they tell us to ‘stay positive’, ‘be courageous’, and ‘you can beat this’. I have even heard oncologist say that the patient failed the chemotherapy treatment. Really? Did we just put ourselves through what can feel like hell getting round upon round of chemotherapy and then deliberately failing to respond to the drug? Do we set out to disappoint our oncologist by refusing to eradicate the cancer cells. We don’t think so.

Do those for whom the chemotherapy has been effective and declared NED (no evidence of disease) fight harder than those whose cancer did not respond to the chemotherapy? Yet family and friends will tell everyone that their loved one has won the fight against the disease. And if they die from the disease our language is that they have ‘lost the fight’. When we frame serious illness as a war, there will be winners and losers. What is the value of this characterization? Why should we participate when some of us are going to be called losers? The use of the battle metaphor implies a level of control that patients simply do not have. For the most part, we don’t know why one person is alive 10 years after the diagnosis of advanced cancer, while another dies within months.

Maureen Kenny in her blog about having breast cancer writes, “It seems if you’ve got cancer you’re almost always seen as battling or fighting it, more often than not bravely. We never hear of anyone dying of the disease after a lackluster, take or it or leave it, weak-willed tussle. Can’t we be allowed just to have cancer and get on with it?”

It seems that we either die fighting the good fight or be the one who chooses to withdraw treatment before “the end” by giving up and giving in. This type of victim blaming seems to only apply in the case of cancer and not to other serious illnesses. If we die from complications of heart disease have, do we lose our battle with heart disease?

There is actual harm in our “battle” mentality

Unfortunately, the continuous urge to win the battle extends to oncologists, who actively treat patients for too long. The fact is that 8% of patients receive chemotherapy within 2 weeks of dying of cancer, and 62% within 2 months.

Late chemotherapy is associated with decreased use of hospice, greater use of emergency interventions (including resuscitation), and increased risk of dying in an intensive care unit rather than at home, which reflects the need to battle until the end.

Most cancer treatments are toxic: they can cause depression of the immune system, fatigue, rash, nausea, vomiting, bankruptcy, and nerve pain, just to name a few. Yet, we are willing to deal with these these side-effects as a trade-off for “hope”—but how honest are the about the true potential benefit of the treatment?

Dr. Lee Ellis and team wrote in a JAMA article that for “many therapies, there is little evidence that life is substantially prolonged (for argument’s sake, let us define “substantial” as 2 months or longer). We have seen patients who are determined to win their battle. As they turn from treatment to treatment, they are not spending time with loved ones; rather, they are chasing the illusive “win,” a path that affects not only them but also their family and caregivers, as well as family finances.”

Using the battle metaphor implies that if a patient fights hard enough, smart enough, and/or long enough, he or she will be able to win the war. Unfortunately, and with rare exceptions, patients with metastatic cancer cannot conquer cancer (win the “war”) no matter how hard they fight.

– Ellis et al, Losing “Losing the Battle With Cancer”

You Beat Cancer by the Manner in Which You Live

Stuart Scott died of cancer at the age of 49, 7 years after his initial diagnosis and aggressive therapy. At the ESPY awards, during his cancer treatment, he told the audience, “When you die, it does not mean that you lose to cancer. You beat cancer by how you live, why you live, and in the manner in which you live.”

Live every day like it was your last one, and one day, you’re going to be right. Live well, in joy and mindfulness of the life you have.

References:

- Why cancer is not a war, fight, or battle (opinion) | CNN

- Tomasetti, C., Vogelstein, B., Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science347,78-81(2015). DOI:10.1126/science.1260825

- Bad Luck of Random Mutations Plays Predominant Role in Cancer, Study Shows – 01/01/2015 (hopkinsmedicine.org)

- Why do we have to “battle” cancer? | iamtheoneineight (wordpress.com)

- Ellis, L.M., Blanke, C. D., and Roach, N. Losing “Losing the Battle With Cancer”. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(1):13–14. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2014.188.

- Foss M. Hannah Storm breaks Stuart Scott’s passing to the world in incredible eulogy. USA Today. January 4, 2015. http://ftw.usatoday.com/2015/01/stuart-scott-hannah-storm-espn-eulogy.

- Cancer Stigma and Silence Around the World (Lance Armstrong Foundation)

Related Episodes:

- S1E31: Recurrent Cancer

- S4E20: Palliative Chemotherapy: Is it ever appropriate for people with end-stage cancer?

- S3E42: We All Want Impossible Things – with Catherine Newman

- S3E37: What Can a Mindfulness Practice Offer You?

- S3E43: How Accepting Death Can Improve Your Life

Living in Mindfulness

Speaking of mindfulness, David joins us again to talk about his journey with meditation and mindfulness. It was difficult at first, but he shares the incredible benefits he has seen, including lowering his blood pressure, more attentiveness to family and friends, and more enjoyment of the little moments in each day. Below are some resources he wanted to share with you.

Mindfulness resources:

- Mindful.org – Getting Started

- UCLA – Free guided meditations

- Veterans Administration – Mindfulness Coach

- Headspace

Recipe of the Week

Speaking of battles, we bring you a recipe this week from the Civil War Era – Ginger Nuts. Get the recipe and a bit of history here. If you’re an era buff, she has a lot of other recipes you may like!

https://blog.feedspot.com/palliative_care_podcasts/

Everyone Dies: and yes, it is normal!

Everyone Dies (and yes, it is normal) is a story about a young boy named Jax who finds something special on the beach where he and his grandpa Pops are enjoying a wonderful day. Pops helps Jax understand that death is a normal part of life. This book provides an age appropriate, non-scary, comfortable way to introduce the important topic of mortality to a preschool child. Its simple explanation will last a lifetime. Autographed copies for sale at: www.everyonediesthebook.com. Also available at Amazon

Mourning Jewelry

We offer a way to memorialize your loved one or treasured pet with a piece of handmade jewelry. When people comment on it and the wearer can say for example “I received this when my mother died” which opens the conversation about this loss. All our jewelry is made with semi-precious stones and beads, vintage beads, and pearls. You can choose between earrings or bracelets and the color family. Learn More